The first in an occasional series

Uposatha Day

Today is the full moon (3:02 GMT)

Venerable Samahita, a Sri Lankan monk, runs eBuddha forum, and also has a homepage called "What the Buddha Said" (2023: The page seems to be gone). In a recent e-mail, he informed us:

This Esala Poya day is the full-moon of July, which is noteworthy since on this celebrated day:

- The Blessed Buddha preached his First Sermon: The Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta.

- The Bodhisatta was conceived in Queen Maya dreaming a white elephant entered her side.

- The Blessed Buddha made the Great Withdrawal from the world at the age of 29 years.

- The Blessed Buddha performed the Twin Miracle (yamaka-patihariya) of dual appearance.

- The Blessed Buddha explained the Abhidhamma in the Tavatimsa heaven to his mother.

- The ordination of Prince Arittha at Anuradhapura, under arahat Mahinda on Sri Lanka.

- The foundation of the celebrated Mahastupa & enshrinement of relics by King Dutugemunu.

- The next day the yearly 3 months rains retreat (vassa) of Buddhist Bhikkhus start.

Venerable Samahita goes on to point out that this is a particularly auspicious day to "Take Refuge" (become a Buddhist), and gives a ceremony for doing so at home. The full letter can be read here. And if you do take refuge, you can make a public declaration of it on his homepage here (2023: Again, the links are gone.).

Why is this a particularly good day to join? Notice the first point above: It is the day the Buddha preached his first sermon. Which means it is the day he ordained his first disciples, the Five Monks. By "coincidence," we are studying that same sutra in my new Sutra Study right now! And last Friday I posted responses to Lesson 1, which included a discussion of the significance of those Five Monks. Wonderful how it all falls together!

(Read more about Poya--the Sinhala word for "uposatha"--days in Sri Lanka here.)

I have been thinking deeply about the story I urged you to read last Saturday, "The Miracle of Purun Bhagat". I am absolutely captivated by the idea of a man who can attain the highest degree of success in the world, and then walk away to pursue inner values without a shred of regret.

It reminds me of any number of stories in Japan. The pattern is this: A man has a crisis, a tragedy strikes. Result? He becomes a monk. It's almost a cliché. But the fact is, in these stories, the man only becomes a monk after a tragedy. Purun Dass does so after success!

This is the embodiment of a famous story in the Upanishads (Svetasvatara Upanishad 4:6-7 and Mundaka Upanishad 3:1-2 tell the identical story):

Two birds, inseparable friends, cling to the same tree. One of them eats the sweet fruit, the other looks on without eating.

On the same tree a man sits grieving, immersed, bewildered, by his own impotence (an-îsâ). But when he sees the other lord (îsa) contented, and knows his glory, then his grief passes away.

That's Max Muller's late 19th-century translation in The Sacred Books of the East.

Swami Sivananda translated the first of the two verses thus:

Two birds of beautiful plumage -- inseparable friends -- live on the same tree. Of these two one eats the sweet fruit while the other looks on without eating.

So the story of "The Two Birds" is brief in the extreme. In fact, it is virtually opaque--out of context. The second verse, about The Grieving Man who is an-isa or "not-God" is the key. He is the bird who participates in the world. God, what Swami Sivananda calls Brahman--God without attributes--is the second bird, who watches but does not participate.

According to Wikipedia, the Swami commented:

...the first bird represents the individual soul, while the second represents Brahman or God. The soul is essentially a reflection of Brahman. The tree represents the body. The soul identifies itself with the body, reaps the fruits of its actions, and undergoes rebirth. The Lord alone stands as an eternal witness, ever contented, and does not eat, for he is the director of both the eater and the eaten.

Another commentary, by Sri Sri Sri Chandrasekharendra Saraswathi, spells it out even more clearly:

The Upanisadic story speaks of two birds perched on the branch of a pippala tree. One eats the fruit of tree while the [other] merely watches its companion without eating. The pippala tree stands for the body. The first bird represents a being that regards himself as the jivatman or individual self and the fruit it eats signifies sensual pleasure. In the same body (symbolized by the tree) the second bird is to be understood as the Paramatman [Sivananda's Brahman]. He is the support of all beings but he does not know sensual pleasure. Since he does not eat the fruit he naturally does not have the same experience as the jivatman (the first). The Upanisad speaks with poetic beauty of the two birds. He who eats the fruit is the individual self, jiva, and he who does not eat is the Supreme Reality, the one who knows himself to be the Atman.

I am preparing a talk to be given this autumn entitled simply "How to Be Happy." This idea of The Two Birds is one of the keys to this happiness.

|

| The Two Birds, woven in a carpet |

How? Here's a quote from Joseph Campbell (in The Power of Myth):

There is a plane of consciousness where you can identify yourself with that which transcends pairs of opposites.

"Pairs of opposites," like good vs evil, joy vs suffering, success vs failure.

What happens, we ask, if we turn our attention from the affairs of This World to those of That? What happens when we identify ourselves, not with the bird who eats, but with the bird who watches? In an unattributed quote (in an article entitled "Hinduism 101: Shedding Some Light on Light Shedding" [2023: gone]), we read:

Henry [David] Thoreau, the transcendentalist, put it like this, "I am conscious of the presence of a part of me, which, (as it were), is not part of me, but a spectator, sharing no experience, but taking note of it..."

The author then continues with a specific recommendation for how to attain this "spectator" position:

For the Hindu it is possible to develop this spectator, this Observer I, through separation. By separating yourself from what you are doing in your life you become more aware of yourself, tend to look at your life more objectively so you don't get caught up in the ego's illusions and fantasies, and you fulfill Socrates advise [sic] to "Know Thyself." A very practical way to do this is to sit for a few minutes each day in silence and inactivity focusing solely on the experience of breathing in and out. The best way to learn about anyone is to be alone with them, including yourself.

This is the Vedanta expression of the classic Buddhist concept of Non-Attachment.

Notice that I didn't say "detachment." The distinction usually needs to be spelled out. "Detachment" sounds aloof, cold, uncaring. This is a parody of the true Buddhist position. "Non-attachment" is like the second bird: Not engaged in the action, but nevertheless present to it.

What would non-attachment look like "in action"? Here's a famous Zen (Chan) story:

A beautiful girl in the village was pregnant. Her angry parents demanded to know who was the father. At first resistant to confess, the anxious and embarrassed girl finally pointed to Hakuin, the Zen master whom everyone previously revered for living such a pure life. When the outraged parents confronted Hakuin with their daughter's accusation, he simply replied "Is that so?"

When the child was born, the parents brought it to Hakuin, who now was viewed as a pariah by the whole village. They demanded that he take care of the child since it was his responsibility. "Is that so?" Hakuin said calmly as he accepted the child.

For many months he took very good care of the child until the daughter could no longer withstand the lie she had told. She confessed that the real father was a young man in the village whom she had tried to protect. The parents immediately went to Hakuin to see if he would return the baby. With profuse apologies they explained what had happened. "Is that so?" Hakuin said as he handed them the child.

(Found here, along with an interesting collection of people's reactions to the story. [2023: gone])

You see, Hakuin was not disengaged from the people around him; he was just unaffected by their opinions of him. As the new-agey L.A. saying goes, "What you think of me is none of my business!" He was not detached, as in uncaring; look at the sacrifice he made for that baby's well-being. He was compassion personified, despite the disapproval of the crowd. But regarding their behavior he was non-attached, in the way the second bird was unaffected by the first bird's actions.

The Pali word for non-attachment, virāga (the first a is long), means "the absence of raga," and raga means "excitement, passion." By extension, raga is lust, desire, and craving for existence. Virāga, then, is the antidote to the "desire" which the Buddha speaks of in the Second Noble Truth, when he says that suffering is the result of desire (also called "craving" and "thirst").

Look, we just arrived at how to be happy: Suffering comes from desire; non-attachment eliminates desire, and, thus, suffering.

Now, everyone wants to avoid suffering. But what is the first bird doing? He's not suffering; he's enjoying a fruit. So a tougher lesson is to learn not to be attached to joy, either! Because it will certainly pass, leading again to--you guessed it--suffering! The Buddha described suffering as, among other things, both "association with the unpleasant" and "dissociation from the pleasant." To have something good and lose it, as we all know, can sometimes be worse than never having it at all.

But what if we could learn to greet both suffering and joy equally? This is equanimity. "En-joy," yes, but don't grasp at it. As William Blake wrote:

He who binds to himself a joy

Does the winged life destroy;

But he who kisses the joy as it flies

Lives in Eternity's sunrise.

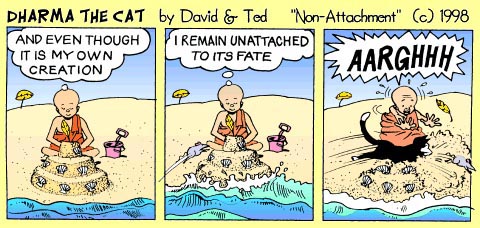

I know, it ain't easy. There are lots of illustrations of this, like this cartoon. (The whole series is great):

So one important point about non-attachment is that we must avoid attachment both to positive and negative experiences (Cletus will have something to say about this later this week. [Oops! Never did.])

A second point is that non-attachment is not non-action. We still must participate in the world. This is where the equally important Buddhist idea of compassion comes from. And this is not just a religious thing. Hear the great bodhisattva Albert Einstein (though this seems to have been two quotations joined together):

A human being is a part of a whole, called by us universe, a part limited in time and space. He experiences himself, his thoughts and feelings as something separated from the rest... a kind of optical delusion of his consciousness. This delusion is a kind of prison for us, restricting us to our personal desires and to affection for a few persons nearest to us. Our task must be to free ourselves from this prison by widening our circle of compassion to embrace all living creatures and the whole of nature in its beauty.

(An interesting aside: There is a quote floating around spuriously attributed to Einstein: "Buddhism has the characteristics of what would be expected in a cosmic religion for the future: It transcends a personal God, avoids dogmas and theology; it covers both the natural and the spiritual, and it is based on a religious sense aspiring from the experience of all things, natural and spiritual, as a meaningful unity." It may not be anything Al said, but I can certainly give it a big "Amen!")

Back to the idea at hand, that non-attachment is not non-action: The word dharma has a wide range of meanings. In Buddhism, the most commonly grasped of these many meanings is "the teachings of the Buddha." In the traditions we refer to collectively as "Hinduism," the preferred meaning seems at first to be quite different: it is generally understood as "duty." But here, I think, the two meanings coincide. It is our duty to practice compassion, a key component of the Buddha's teaching.

One cannot think of the story of "The Two Birds" without thinking of Lord Krishna's instructions to Arjuna in The Bhagavad Gita. In Chapter 4, he gives a divine view of the relationship between the first bird (action, doing your duty, fulfilling your dharma) and the second (non-attachment):

|

| Lord Krishna instructs Arjuna |

The awakened sages call a person wise when all his undertakings are free from anxiety about results; all his selfish desires have been consumed in the fire of knowledge. The wise, ever satisfied, have abandoned all external supports. Their security is unaffected by the results of their action; even while acting, they really do nothing at all [i.e., nothing producing karma].

In fact, many have drawn this parallel: The first bird is Arjuna, who participates in the struggles of the world. The second, then, is Lord Krishna, who observes.

To act, and act fully and without reservation, and yet to be free of concern about the results: This is living in the spirit of Lila, recognizing this world as the Play of the Gods, or, as Jung said, seeing things "as if": I don't know if there is a God, but if I live as if there were, my life will be better; I don't know if my wife loves me, but if I live as if she did, I will have a happier marriage; and so on.

An interesting example of this concept of "work hard, without attachment to results" is summed up in a Japanese word: shoganai. Surely no people are more diligent and industrious (sometimes to the point of obsession and even death) than the Japanese. And yet, sometimes, matters are taken out of one's hands: an earthquake strikes, a tsunami washes away years of effort. And what, in such cases, do the Japanese do? They shrug, raise their hands skyward, and say "Shoganai!" Which means, roughly, "What can be done?" or "It can't be helped." The Filipinos have a similar expression, "Bahala na!" or "[It's up to ] God." "Come what may," a kind of "Que sera, sera-- What will be, will be." These are the first glimmerings of the right attitude of non-attachment.

And then there are the old shortcuts: "Will anyone really care about this a hundred years from now?" and "Someday we're gonna look back on this and laugh."

* * * * * * * *

* * * * * * * *

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please leave me a message; I can't wait to hear from you!